Giant is even larger than you might imagine. It’s an incomparable addition to the Great American Epic movie playlist. It was much more honest than I expected, treating some of today’s most sensitive subjects with cleverity, humor, and uncompromising seriousness. Ultimately a wrestling match between three generations of tradition vs progress, I found Giant to be a mostly humanizing, hopeful work, yet quite politically subversive for it’s era (though obviously far from alone). Hudson, Taylor, and Hopper are all outstanding and perfectly cast. I’m already excited to revisit it again in the near future!

While all this is striking and worth a further deep dive, I’ve really only thought about one thing since I watched it five weeks ago.

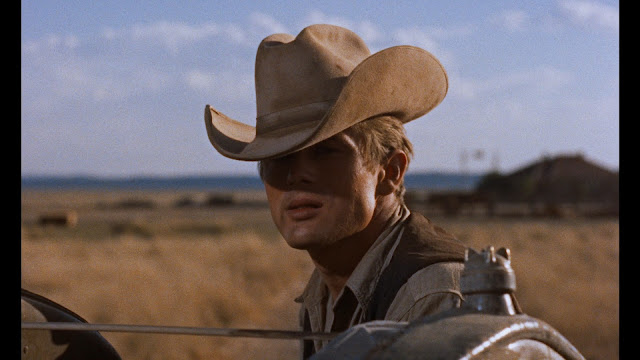

James Dean.

James Dean.

I’ve seen the other two Dean films, but I’d held out on this. It’s a quirk of mine, but sometimes I won’t finish a good book because then it will be finished. Watching this movie means there are no more James Dean films to experience for the first time. Also, I wasn’t a fan of George Steven’s classic Western, Shane, so I felt resistant toward this 3 1/2 hour undertaking. But here we are, and there is really nothing quite like it. Nothing really like James Dean, his presence, various postures, glares, and complete unpredictability. I don't have the language for it, tbh, but I discovered a short essay from 1956, written by Francois Truffaut (student of Andre Bazin), called James Dean is Dead from his book The Films of My Life. Truffaut says, "With James Dean everything is grace, in every sense of the word." Below is a large chunk of the essay, and if you are a fan of Dean's work, you will appreciate it. Enjoy!

...

“James Dean's acting flies in the face of fifty years of filmmaking; each gesture, attitude, each mimicry is a slap at the psychological tradition. Dean does not "show off" the text by understatement like Edwige Feuillère; he does not evoke its poetry, like Gérard Philipe; he does not play with it mischievously like Pierre Fresnay. By contrast, he is anxious not to show that he understands perfectly what he is saying, but that he understands it better than the director did. He acts something beyond what he is saying; he plays alongside the scene; his expression doesn't follow the conversation. He shifts his expression from what is being expressed in the way that a consummately modest genius might express profound thoughts self-deprecatingly, as if to excuse himself for his genius, so as not to make a nuisance of himself.

There were special moments when Chaplin reached the ultimate in mime: he became a tree, a lamppost, an animal-skin rug next to a bed. Dean's acting is more animal than human, and that makes him unpredictable. What will his next gesture be? He may keep talking and turn his back to the camera as he finishes a scene; he may suddenly throw his head back or let it droop; he may raise his arms to heaven, stretch them forward, palms up to convince, down to reject. He may, a single scene, appear to be the son of Frankenstein, a little squirrel, a cowering urchin or a broken old man. His nearsighted look adds to the feeling that he shifts between his acting and the text; there is a vague fixedness, almost a hypnotic half-slumber.

When you have the good luck to write for an actor of this sort, an actor who plays his part physically, carnally, instead of filtering everything through his brain, the easiest way to get good results is to think abstractly. Think of it this way: James Dean is a cat, a lion, or maybe a squirrel. What can cats, lions and squirrels do that is most unlike humans? A cat can fall from great heights and land on its paws; it can be run over without being injured; it arches its back and slips away easily. Lions creep and roar; squirrels jump from one branch to another. So, what one must write are scenes in which Dean creeps (amid the beanstalks), roars (in a police station), leaps from branch to branch, falls from a great height into an empty pool without getting hurt. I like to think this is how Elia Kazan, Nicholas Ray, and, I hope, George Stevens proceeded.

Dean's power of seduction was so intense that he could have killed his parents every night on the screen with the blessing of the snobs and the general public alike. One had to witness the indignation in the movie house when, in East of Eden, his father refuses to accept the money that Cal earned with the beans, the wages of love.

More than just an actor, James Dean, like Chaplin, became a personality in only three films: Jimmy and the beans and at the country fair, Jimmy on the grass, Jimmy in the abandoned house. Thanks to Elia Kazan's and Nicholas Ray's sensitivity to actors, James Dean played characters close to the Baudelairean hero he really was.

The underlying reasons for his success? With women, the reason is obvious and needs no explanation. With young men, it was because they could identify with him; this is the basis for the commercial success of his films in every country of the world. It is easier to identify with James Dean than with Humphrey Bogart, Cary Grant, or Marlon Brando. Dean's personality is truer. Leaving a Bogart movie, you may pull your hat brim down; this is no time for someone to hassle you. After a Cary Grant film, you may clown around on the street; after Brando, lower your eyes and feel tempted to bully the local girls. With Dean, the sense of identification is deeper and more complete, because he contains within himself all our ambiguity, our duality, our human weaknesses.

Once again, we have to go back to Chaplin, or rather Charlie. Charlie always starts at the bottom and aims higher. He is weak, despised, left out. He fails in all his efforts; he tries to sit down to relax and ends up on the ground, he's ridiculous in the eyes of the woman he courts or in the eyes of the brute he wants to tame. What happens at this point is a pure gift: Chaplin will avenge himself and win out. Suddenly he begins to dance, skate, spin better than anyone else, and now he eclipses everyone, he triumphs, he changes the mood and has all the jeerers on his side.

What started out as an inability to adapt becomes super-adeptness. The entire world, everybody and everything that had been against him, is now at his service. All this is true of Dean, too, but we must take into account a fundamental difference: never do we catch the slightest look of fear. James Dean is beside everything; in his acting neither courage nor cowardice has any place any more than heroism or fear. Something else is at work, a poetic game that lends authority to every liberty even encourages it. Acting right or wrong has no meaning when we talk about Dean, because we expect a surprise a minute from him. He can laugh when another actor would cry - or the opposite.

There were special moments when Chaplin reached the ultimate in mime: he became a tree, a lamppost, an animal-skin rug next to a bed. Dean's acting is more animal than human, and that makes him unpredictable. What will his next gesture be? He may keep talking and turn his back to the camera as he finishes a scene; he may suddenly throw his head back or let it droop; he may raise his arms to heaven, stretch them forward, palms up to convince, down to reject. He may, a single scene, appear to be the son of Frankenstein, a little squirrel, a cowering urchin or a broken old man. His nearsighted look adds to the feeling that he shifts between his acting and the text; there is a vague fixedness, almost a hypnotic half-slumber.

When you have the good luck to write for an actor of this sort, an actor who plays his part physically, carnally, instead of filtering everything through his brain, the easiest way to get good results is to think abstractly. Think of it this way: James Dean is a cat, a lion, or maybe a squirrel. What can cats, lions and squirrels do that is most unlike humans? A cat can fall from great heights and land on its paws; it can be run over without being injured; it arches its back and slips away easily. Lions creep and roar; squirrels jump from one branch to another. So, what one must write are scenes in which Dean creeps (amid the beanstalks), roars (in a police station), leaps from branch to branch, falls from a great height into an empty pool without getting hurt. I like to think this is how Elia Kazan, Nicholas Ray, and, I hope, George Stevens proceeded.

Dean's power of seduction was so intense that he could have killed his parents every night on the screen with the blessing of the snobs and the general public alike. One had to witness the indignation in the movie house when, in East of Eden, his father refuses to accept the money that Cal earned with the beans, the wages of love.

More than just an actor, James Dean, like Chaplin, became a personality in only three films: Jimmy and the beans and at the country fair, Jimmy on the grass, Jimmy in the abandoned house. Thanks to Elia Kazan's and Nicholas Ray's sensitivity to actors, James Dean played characters close to the Baudelairean hero he really was.

The underlying reasons for his success? With women, the reason is obvious and needs no explanation. With young men, it was because they could identify with him; this is the basis for the commercial success of his films in every country of the world. It is easier to identify with James Dean than with Humphrey Bogart, Cary Grant, or Marlon Brando. Dean's personality is truer. Leaving a Bogart movie, you may pull your hat brim down; this is no time for someone to hassle you. After a Cary Grant film, you may clown around on the street; after Brando, lower your eyes and feel tempted to bully the local girls. With Dean, the sense of identification is deeper and more complete, because he contains within himself all our ambiguity, our duality, our human weaknesses.

Once again, we have to go back to Chaplin, or rather Charlie. Charlie always starts at the bottom and aims higher. He is weak, despised, left out. He fails in all his efforts; he tries to sit down to relax and ends up on the ground, he's ridiculous in the eyes of the woman he courts or in the eyes of the brute he wants to tame. What happens at this point is a pure gift: Chaplin will avenge himself and win out. Suddenly he begins to dance, skate, spin better than anyone else, and now he eclipses everyone, he triumphs, he changes the mood and has all the jeerers on his side.

What started out as an inability to adapt becomes super-adeptness. The entire world, everybody and everything that had been against him, is now at his service. All this is true of Dean, too, but we must take into account a fundamental difference: never do we catch the slightest look of fear. James Dean is beside everything; in his acting neither courage nor cowardice has any place any more than heroism or fear. Something else is at work, a poetic game that lends authority to every liberty even encourages it. Acting right or wrong has no meaning when we talk about Dean, because we expect a surprise a minute from him. He can laugh when another actor would cry - or the opposite.

He killed psychology the day he appeared on the set.

With James Dean everything is grace, in every sense of the word. That's his secret. He isn't better than everybody else; he does something else, the opposite; he protects his glamour from the beginning to end of each film. No one has ever seen Dean walk; he ambles or runs like a mailman's faithful dog (think of the opening of East of Eden). Today's young people are represented completely in James Dean, less for the reasons that are usually given- violence, sadism, frenzy, gloom, pessimism, and cruelty than for other reasons that are infinitely more simple and everyday: modesty, continual fantasizing, a moral purity not related to the prevailing morality but in fact stricter, the adolescent's eternal taste for experience, intoxication, pride, and the sorrow at feeling "outside," a simultaneous desire and refusal to be integrated into society, and finally acceptance and rejection of the world, such as it is.

No doubt Dean's acting, because of its contemporaneous quality, will start a new Hollywood style, but the loss of this young actor is irreparable; he was perhaps the most inventively gifted actor in films.”

With James Dean everything is grace, in every sense of the word. That's his secret. He isn't better than everybody else; he does something else, the opposite; he protects his glamour from the beginning to end of each film. No one has ever seen Dean walk; he ambles or runs like a mailman's faithful dog (think of the opening of East of Eden). Today's young people are represented completely in James Dean, less for the reasons that are usually given- violence, sadism, frenzy, gloom, pessimism, and cruelty than for other reasons that are infinitely more simple and everyday: modesty, continual fantasizing, a moral purity not related to the prevailing morality but in fact stricter, the adolescent's eternal taste for experience, intoxication, pride, and the sorrow at feeling "outside," a simultaneous desire and refusal to be integrated into society, and finally acceptance and rejection of the world, such as it is.

No doubt Dean's acting, because of its contemporaneous quality, will start a new Hollywood style, but the loss of this young actor is irreparable; he was perhaps the most inventively gifted actor in films.”

...

Highlights are mine.